- by Todd C. Wehner

- Department of Horticultural Science

- North Carolina State University

- Raleigh, NC 27695-7609

Introduction

Watermelon (Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Matsum. & Nakai) is a major cucurbit crop that accounts for 6.8% of the world area devoted to vegetable crops (FAO, 2002). Watermelon is grown for its fleshy, juicy, and sweet fruit. Mostly eaten fresh, they provide a delicious and refreshing dessert especially in hot weather. The watermelon has high lycopene content in the red-fleshed cultivars: 60% more than tomato. Lycopene has been classified as a useful in the human diet for prevention of heart attacks and certain types of cancer (Perkins-Veazie et al., 2001).

Watermelon (Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Matsum. & Nakai) is a major cucurbit crop that accounts for 6.8% of the world area devoted to vegetable crops (FAO, 2002). Watermelon is grown for its fleshy, juicy, and sweet fruit. Mostly eaten fresh, they provide a delicious and refreshing dessert especially in hot weather. The watermelon has high lycopene content in the red-fleshed cultivars: 60% more than tomato. Lycopene has been classified as a useful in the human diet for prevention of heart attacks and certain types of cancer (Perkins-Veazie et al., 2001).

Watermelon is native to central Africa where it was domesticated as a source of water, a staple food crop, and an animal feed. It was cultivated in Africa and the Middle East for more than 4000 years, then introduced to China around 900 AD, and finally brought to the New World in the 1500s. There are 1.3 million ha of watermelon grown in the world, with China and the Middle Eastern countries the major consumers. China is the largest watermelon producer, with 68.9% of the total production. The other major watermelon producing countries are Turkey, Iran, Egypt, United States, Mexico and Korea (FAO, 2002). In the United States, watermelon is used fresh as a dessert, or in salads. U.S. production is concentrated in Florida, California, Texas, and Georgia (USDA, 2002), increasing from 1.2 M tons in 1980 to 3.9 M tons in 2002, with a farm value of $329 million (USDA, 2002).

Watermelon is a useful crop species for genetic research because of its small genome size, and the many available gene mutants. Genome size of watermelon is 424 million base pairs (Arumuganathan and Earle 1991). DNA sequence analysis revealed high conservation useful for comparative genomic analysis with other plant species, as well as within the Cucurbitaceae (Pasha 1998). Like some of the other cultivated cucurbits, watermelon has much genetic variability in seed and fruit traits. Genetic investigations have been made for some of those, including seed color, seed size, fruit shape, rind color, rind pattern, and flesh color.

This is the latest version of the gene list for watermelon. The watermelon genes were originally organized and summarized by Poole (1944). The list and updates of genes for watermelon have been expanded and published by Robinson et al. (1976), the Cucurbit Gene List Committee (1979, 1982, and 1987), Henderson (1991 and 1992), Rhodes and Zhang (1995), and Rhodes and Dane (1999). This current gene list provides an update of the known genes of watermelon, with 163 total mutants grouped into seed and seedling mutants, vine mutants, flower mutants, fruit mutants, resistance mutants, protein (isozyme) mutants, DNA (RFLP and RAPD) markers, and cloned genes.

Researchers are encouraged to send reports of new genes, as well as seed samples of lines containing the gene mutant to the watermelon gene curator (Cecilia McGregor), or to the assistant curator (Todd C. Wehner). Please inform us of omissions or errors in the gene list. Scientists should consult the list as well as the rules of gene nomenclature for the Cucurbitaceae (Cucurbit Gene List Committee, 1982; Robinson et al., 1976) before choosing a gene name and symbol. Please choose a gene name and symbol with the fewest characters that describes the recessive mutant, and avoid use of duplicate gene names and symbols. The rules of gene nomenclature were adopted in order to provide guidelines for naming and symbolizing genes. Scientists are urged to contact members of the gene list committee regarding rules and gene symbols. The watermelon gene curators of the Cucurbit Genetics Cooperative are collecting seeds of the type lines for use by interested researchers, and would like to receive seed samples of any of the lines listed.

This gene list has been modified from previous lists in the following ways: 1) the description of the phenotypes of several of the gene mutants has been expanded, 2) the descriptions for phenotypes of interacting gene loci have been added, 3) some type-lines that carry each allele of each gene locus have been added, 4) the gene mutant lines that are in the curator collections have been identified, 5) genes that have not previously been described have been added: g-2 (Kumar and Wehner, 2011) and YScr, and 6) some errors in gene descriptions or references have been corrected.

Watermelon Gene Lists

- Poole, 1944: 15 genes total

- Robinson et al., 1976: 10 genes added, 25 genes total

- Robinson et al., 1979: 3 genes added, 28 genes total

- Robinson et al., 1982: 2 genes added, 30 genes total

- Henderson, 1987: 3 genes added, 33 genes total

- Henderson, 1991: 3 genes added, 36 genes total (plus 52 molecular markers)

- Rhodes and Zhang, 1995: 3 genes added, 39 genes total (plus 109 molecular markers)

- Rhodes and Dane, 1999: 5 genes added, 44 genes total (plus 111 molecular markers)

- Guner and Wehner, 2003: 8 genes added, 52 genes total

- Wehner, 2007: 8 genes added, 60 genes total

- Wehner, 2012: 2 genes added, 62 genes total

Gene Mutants

Seed and seedling genes

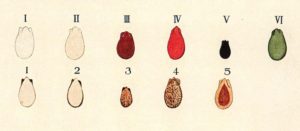

Watermelon seed coat colors include black, brown, tan, white, green, and red. Seeds may have pink or black tips, or black rims (a dark band around the seed periphery). There are reports of other seed coat colors that include one background color with a different foreground color, that makes the seed coat color difficult to classify. Other factors that make it difficult to classify seed coat color include different shades of a single color. Two observers may classify a single phenotype as different colors, or give same name to two different phenotypes. That makes it difficult to review previous studies.

Resarch on watermelon seed coat color began in the 1930s. Kanda (1931) reported the first genetic study of watermelon seed characters including 13 crosses. He described 6 ground colors (white, yellowish white, reddish brown, reddish orange, black, and yellowish green) and 5 patterns (black spot on the seed tip, black dots, black rim, yellow margin on the periphery of the both flat sides, or solid color) and proposed 7 pairs of genes controlling these characters. However, due to the ambiguity of naming the seed coat colors, it is difficult to compare seed coat colors between Kanda and other studies. As a result, the classification of Kanda has not been adopted widely.

McKay (1936) studied the inheritance of tan, green and red seed coat colors in different types (preserving and stock) types of citron, and demonstrated that both tan and green are monogenic dominant over red. The genotypes for tan and red were later assigned by poole et al. (1941) as RRttWW for tan, and rrttWW for red. The genotype rrTTWW was inferred for green (McKay, 1936; Poole, 1944).

Porter (1937) investigated crosses between black-, tan- and white-seeded lines, and reported either two loci or multiple alleles at one locus controlling seed coat color. Black was dominant over clump, tan, and white. The white seed color in ‘Pride of Muscatine’ referred in the paper is formally named “white with tan tip” (Wehner, 2008). This demonstrates the ambiguity of classification of seed coat colors as mentioned above. It is difficult to confirm the results due to this ambiguity when the type lines are no longer available. The white-seeded cultivars used by Porter might have been real white or white with tan tip. Other crosses were studied by Porter only in the F1 generation, which showed the dominance of black over white, red over white, black over green, and green over red. The green over red dominance is consistent with previous report (McKay, 1936). Additionally, Porter also found no linkage among rind toughness, flesh color, or skin color.

Weetman crossed ‘Long Iowa Belle’ (described as light tan with peripheral black banded seeds) with ‘Japan 4’ (described as medium brown, black-dotted seeds) and found the latter was a single dominant allele. These two coat colors were later referred as clump and black, respectively (Poole et al., 1941). The cross between ‘Japan 6’ (the seed color is described as reddish brown, or tan as referred by Poole) and ‘Long Iowa Belle’ showed a 9:3:3:1 segregation ratio in F2, indicating dominant alleles at two loci (Weetman, 1937).

Poole et al. (1941) studied the inheritance of several color types including black, tan, red, clump, white tan-tip, and white pink-tip and found that these phenotypes can be explained by a 3-locus model. The black seed-color is found to be dominant over other colors, consistent with previous reports. Poole et al. proposed three genes r, t and w that interact to determine the seed color. From their crossing experiments, Poole et al. assigned the genotypes RRTTWW for black seeds, RRttWW for tan, RRTTww for clump, RRttww for white tan-tip, rrttWW for red, and rrttww for white pink-tip. They did not have observe genotypes rrTTWW and rrTTww in their experiments. From earlier study and the above genotypes, it can be inferred that rrTTWW should correspond to green seed color (McKay, 1936; Poole, 1944).

In addition, there is a fourth gene, d, suggested by Poole for the stippled surface with numerous black dots (usually with a visible tannish or reddish undercoat). The d gene is a modifying locus for black seed color, and only acts in the RRTTWW genotype, making RRTTWWDD is black, RRTTWWdd is dotted black (Poole, 1941).

Shimotsuma (1963) reported that brown seed color was dominant to white in crosses of 3 wild lines of watermelon. Sharma and Choudhury (1982) showed fuscous black is one gene dominant over white seed coat color. However, it is not clear how the brown, fuscous black and white colors correspond to current color classifications. Additional research is needed to clarify this and other inheritance studies of seed coat colors.

The genes (s) and (l) for short and long seed length (sometimes called small and large seed size) control seed size, with s epistatic to l(Poole et al., 1941). The genotype LL SS gives medium size, ll SS gives long, and LL ss or ll ss gives short seeds. The Ti gene for tiny seed was reported by Tanaka et al. (1995). Tiny seed from ‘Sweet Princess’ was dominant over medium-size seed and controlled by a single dominant gene. The small seed gene behaved in a manner different from Poole’s medium-size seed cultivar, where short was recessive to medium-size seeds. Tanaka et al. (1995) suggested that the Ti gene was different from the s and l genes. Unfortunately, the origin of short- and long-seed genes was not described in Poole’s paper. Tomato seed is shorter and narrower than the short seeded genotype, ll ss, with a width x length of 2.6 x 4.2 mm. The trait is controlled by the ts (Zhang, 1996; Zhang et al., 1994a) gene, with genotype LL ss tsts. The interaction of the four genes for seed size (l, s, Ti and ts) needs to be investigated further. However, the original type-lines for the s and l genes are not available.

Cracked seed coat cr (El-Hafez et al., 1981) is inherited as a single gene that is recessive to smooth seed coat. There is no seed available of the type line, ‘Leeby’, but there are other lines available having a seed cracking trait that may be allelic, such as PI 593350. Egusi seed trait is controlled by the eg gene (Gusmini et al., 2004), and has fleshy pericarp covering the seeds. However, after washing and drying, the seeds are difficult to distinguish from the smooth (noncracked) seeds of the normal type. Pale leaf (pl) is a spontaneous chlorophyll mutant with light green foliage that can be observed as early as the cotyledon stage (Yang, 2006).

Vine genes

Several genes control leaf or foliage traits of watermelon. Nonlobed leaf (nl) has sinuate leaves rather than the lobed leaf type of the typical watermelon (Mohr, 1953). According to nomenclature rules, the trait should be named directly for the mutant trait (sinuate leaves, sn), rather than for the absence of the normal trait (nonlobed, nl).

Seedling leaf variegation slv (Provvidenti, 1994) causes a variegation resembling virus infection on seedlings. It is linked or pleiotropic with Ctr for cool temperature resistance. The yellow leaf (Yl) gene results in yellow leaves, and is incompletely dominant to green leaves (Warid and Abd-El-Hafez, 1976). Delayed green leaf dg (Rhodes, 1986) causes pale green cotyledons and leaves for the first few nodes, with later leaves developing the normal green color. Inhibitor of delayed green leaf (i-dg) makes leaves normal green even when they have the dgdg genotype (Rhodes, 1986). The juvenile albino ja (Zhang et al.,1996b) gene causes reduced chlorophyll in seedling tissues, as well as leaf margins and fruit rind when plants are grown under short day conditions. The dominant gene Sp (Poole, 1944) causes round yellow spots to form on cotyledons, leaves and fruit, resulting in the fruit pattern called moon and stars. For more information on Sp, see the fruit gene section below.

So far, four dwarf genes of watermelon have been identified that affect stem length and plant habit: dw-1 (Mohr, 1956; Mohr and Sandhu, 1975) and dw-1s (Dyutin and Afanas’eva, 1987) are allelic, and dw-1, dw-2 (Liu and Loy, 1972), and dw-3 (Huang et al., 1998) are non-allelic. Dwarf-1 plants have short internodes due to fewer and shorter cells than the normal plant type. Plants with dw-1s have vine length intermediate between normal and dwarf, and the hypocotyls were somewhat longer than normal vine and considerably longer than dwarf. The dw-1s is recessive to normal plant type. Plants with dw-2 have short internodes due to fewer cells than the normal type, and plants with dw-3 have leaves with fewer lobes than the normal leaf.

The golden yellow mutant is controlled by the single recessive gene go, where the stem and older leaves are golden yellow (Barham, 1956). The type line for go is ‘Royal Golden’. One benefit of the go gene is that the fruit become golden yellow as they mature, so it might be useful as an indicator of mature fruit. The gene tl (formerly called branchless, bl) results in tendrilless branches after the 5th or 6th node (Lin et al., 1992; Rhodes et al., 1999; Zhang et al., 1996a). Also, plants have half the number of branches of the normal plant type, vegetative meristems gradually become floral, tendrils and vegetative buds are replaced by flowers (with a large percentage being perfect), and growth becomes determinate.

Flower genes

The andromonoecious gene a (Rosa, 1928) controls monoecious (AA) vs. andromonoecious (aa) sex expression in watermelon. Andromonoecious plants have both staminate and perfect flowers, and appears to be the wild type. Light green flower color is controlled by the single recessive gene, gf (Kwon and Dane, 1999). A gynoecious mutant was discovered in 1996, and is controlled by a single recessive gene, gy (Jiang and Lin, 2007). The gynoecious type may be useful for hybrid production, or for cultivars having concentrated fruit set.

Five genes for male sterility have been reported. Glabrous male sterile (gms) is unique, with sterility associated with glabrous foliage (Ray and Sherman, 1988; Watts, 1962, 1967). A second male sterile ms-1 (Zhang and Wang, 1990) produces plants with small, shrunken anthers and aborted pollen. A third male sterile mutant appeared simultaneously with dwarfism, and the dwarf gene was different from the three known dwarf genes. It was named male sterile dwarf (ms-dw) by Huang et al. (1998). All male sterile genes reduce female fertility as well. These mutants have been used in hybrid production, but have not been as successful as hoped, since they often have low seed yield. A new, spontaneous male sterile mutant (ms-2) with high normal seed set has been identified, and will be more useful for hybrid production (Dyutin and Sokolov, 1990). Recently, a male sterile mutant having unique foliage characteristics (ms-3) was reported by Bang et al. (2006).

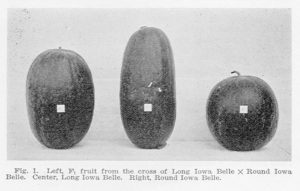

Fruit genes

Fruit shape is controlled by a single, incompletely dominant gene, resulting in fruit that are elongate (OO), oval (Oo), or spherical (oo) (Poole and Grimball, 1945; Weetman, 1937). A single gene controls furrowed fruit surface f (Poole, 1944) that is recessive to smooth (F). The type line for furrowed was not given by Poole, but cultivars such as Stone Mountain and Black Diamond have furrowed fruit surface, in contrast to cultivars such as Mickylee with smooth fruit surface.

Explosive rind (e) causes the fruit rind to burst or split when cut (Porter, 1937), and has been used to make fruit easily crushed by harvest crews for pollenizer cultivars such as SP-1 that have small fruit not intended for harvest. Tough rind (E) is an important fruit trait to give cultivars shipping ability. Rind toughness appears to be independent of rind thickness; the inheritance of rind thickness has not been reported. A single recessive gene su (Chambliss et al., 1968) eliminates bitterness in fruit of C. lanatus, and is allelic to the dominant gene (Su) for bitter flavor in the fruit of the colocynth (Citrullus colocynthis).

Several genes control flesh color in watermelon, producing scarlet red, coral red, orange, salmon yellow, canary yellow, or white. Genes conditioning flesh colors are B (Shimotsuma, 1963), C (Poole, 1944), i-C (Henderson et al., 1998), Wf (Shimotsuma, 1963), y (Porter, 1937) and yO (Henderson, 1989; Henderson et al., 1998). Canary yellow (C) is dominant to other colored flesh (c). Coral red flesh (YCrl) is dominant to salmon yellow (y). Orange flesh (yO) is a member of multiple allelic system at that locus, where YCrl (coral red flesh) is dominant to both yO (orange flesh) and y (salmon yellow), and yO (orange flesh) is dominant to y (salmon yellow). In a separate study, two loci with epistatic interaction controlled white, yellow, and red flesh. Yellow flesh (B) is dominant to red flesh. The gene Wf is epistatic to B, so genotypes WfWf BB or WfWf bb were white fleshed, wfwf BB was yellow fleshed, and wfwf bb was red fleshed. Canary yellow flesh is dominant to coral red, and i-C inhibitory to C, resulting in red flesh. In the absence of i-C, C is epistatic to Y.

A single dominant gene, scarlet red produces the scarlet red flesh color (YScr) of ‘Dixielee’ and ‘Red-N-Sweet’ instead of the lighter, coral red (YCrl) flesh color of ‘Angeleno Black Seeded’ (Gusmini and Wehner, 2006). Scarlet red flesh (YScr) is dominant to coral red flesh (YCrl), orange flesh (yO) and salmon yellow flesh (y). The gene YScr is from ‘Dixielee’ and ‘Red-N-Sweet’, YCrl is from ‘Angeleno’ (black seeded), yO is from ‘Tendersweet Orange Flesh’, and y is from ‘Golden Honey’.

Although flesh color is shown to be controlled by single genes, the fruit in a segregating generation from a cross between two different inbreds is often confusing. Often there are different flesh colors in different areas of the same fruit. One possible hypothesis to explain the presence of the abnormal types is that the expression of the pigment is caused by several different genes, one for each area of the fruit. Thus, the mixed colorations would have been caused by recombination of these genes. It may be useful to have a separate rating of the color of different parts of the flesh to determine whether there are genes controlling the color of each part: the endocarp between the carpel walls and the mesocarp (white rind); the flesh within the carpels, originating from the stylar column; and the carpel walls.

Fruit rind pattern genes

The gene Sp produces spotted fruit, making interesting effects as found on cultivars such as ‘Moon and Stars’ (Poole, 1944). The type line for the Sp gene is ‘Moon and Stars’. There are several cultivars having the term ‘Moon and Stars’ in their name, apparently having different genetic background plus the Sp gene, so that should be taken into account when doing genetic studies. The Sp trait is difficult to recognize on the fruit when the fruit are solid light green in color, but is easy to observe on solid medium green, solid dark green, gray, or striped fruit (Gusmini and Wehner, 2006). Golden yellow was inherited as a single recessive gene go (Barham, 1956) derived from ‘Royal Golden’ watermelon. The immature fruit had a dark green rind which becomes more golden yellow as the fruit matures. The stem and older leaves also become golden yellow, and the flesh color changes from pink to red.

An unusual stripe pattern is found on ‘Navajo Sweet’ called intermittent stripes, with gene symbol ins (Gusmini and Wehner, 2006). The recessive genotype produces narrow dark stripes at the peduncle end of the fruit that become irregular in the middle and nearly absent at the blossom end of the fruit. Stripes on normal fruit, such as ‘Crimson Sweet’ are fairly uniform from peduncle to blossom end. The yellow belly, or ground spot, on ‘Black Diamond Yellow Belly’ is controlled by a single dominant gene, Yb. The recessive genotype, ‘Black Diamond’ has a ground spot that is white (Gusmini and Wehner, 2006).

Weetman (1937) proposed that three alleles at a single locus determined rind pattern. The allelic series was renamed to G, gs, and g by Poole (1944), since g was used to name the recessive trait ‘green’, rather than D for the dominant trait ‘dark green’. The gs gene produces a striped rind, but the stripe width (narrow, medium, and wide stripe patterns) has not been explained as yet. Porter (1937) found that dark green was completely dominant to light green (yellowish white, in his description) in two crosses involving two different dark green cultivars (‘Angeleno’ and ‘California Klondike’). He reported incomplete dominance of dark green in the cross ‘California Klondike’ x ‘Thurmond Gray’, the latter cultivar being described as yellowish green. Thus, gray rind pattern should be described further as either yellowish green (‘Thurmond Gray’) or yellowish white (‘Snowball’). Rind color is controlled by a two-gene system, with G-1G-1 G-2G-2 producing the solid dark green of ‘Mountain Hoosier’ and ‘Early Arizona’, and g-1g-1 g-2g-2 producing the light green of ‘Minilee’ (Kumar and Wehner, 2011). The double recessive produces light green; otherwise the rind is solid dark green (with 15 solid dark green:1 light green in the F2).

The watermelon gene p for pencilled rind pattern has been reported in the gene lists since 1976 (Robinson et al. 1976). The name “penciled” first appeared in 1944 to describe inconspicuous lines on self-colored rind of ‘Japan 6’ (Poole, 1944), but the spelling was changed later to “pencilled” in the gene lists. The cross ‘Japan 6’ x ‘China 23’ was used by Weetman to study the inheritance of solid light green vs. striped rind, and lined (later renamed pencilled) vs. netted rind (Weetman, 1937). ‘Japan 6’ had solid light green rind with inconspicuous stripes, usually associated with the furrow. ‘China 23’ had dark green stripes on a light green background and a network running through the dark stripes (netted type). Weetman confirmed his hypothesis of two independent genes regulating the presence of stripes and the pencilled vs. netted pattern, recovering four phenotypic classes in a 9:3:3:1 ratio (striped, netted : striped, pencilled : non-striped, netted : non-striped, pencilled) in the F2 generation and in a 1:1:1:1 ratio in the backcross to the double recessive non-striped, pencilled ‘Japan 6’. However, Weetman did not name the two genes.

Seeds of the two type lines used by Weetman (‘Japan 6’ and ‘China 23’) are not available, nor are Porter’s data and germplasm, thus making it difficult to confirm the inheritance of the p gene or to identify current inbreds allelic to pencilled and netted rind patterns. In 1944, Poole used the experiment of Weetman to name the single recessive gene p for the lined (pencilled, or very narrow stripe) type. The inheritance of the p gene was measured by Weetman against the netted type in ‘China 23’ and not a “self-colored” (or solid green) type as reported by Poole. Previously, Porter reported that studies of rind striping were underway and specifically cited a pencilled pattern in the F1of the cross ‘California Klondike’ x ‘Golden Honey’ (Porter, 1937). Probably, the P allele produces the netted type, as originally described by Weetman.

The m gene for mottled rind was first described by Weetman in ‘Long Iowa Belle’ and ‘Round Iowa Belle’ (Weetman, 1937). Weetman described the rind as “medium-dark green with a distinctive greenish-white mottling”, the ‘Iowa Belle’ (IB) type. In the cross ‘Iowa Belle’ X ‘China 23’, Weetman observed that the IB type was inherited as a single recessive gene. However, in the cross ‘Iowa Belle’ X ‘Japan 6’, he recovered the two parental types (IB and non-IB, respectively) along with an intermediate type (sub-IB), described as inconspicuous mottling. In the backcross to ‘Iowa Belle’ (the recessive parent for the mottled rind), though, the traits segregated with a perfect fit to the expected 1:1 ratio. He explained the presence of the intermediate type as determined by interfering genes from ‘Japan 6’. There was no other mention of the IB-type until Poole (1944) attributed its inheritance to the m gene from ‘Iowa Belle’, based on the article by Weetman. ‘Iowa Belle’ is not currently available and the IB mottling has not been identified in other mutants since the 1937 study by Weetman.

The homozygous genotypes produced by the genes known to regulate rind color and pattern in watermelon should have the following phenotypes (type-line shown in parentheses): GG MM PP or GG MM pp = solid dark green (‘Angeleno’), GG mm = mottled dark green (‘Iowa Belle’, not available), gg MM = solid light green (‘?’), gg MM pp = pencilled (‘Japan 6’, not available), gg PP = yellowish green or gray (‘Thurmond Gray’), and gsgs PP = medium-stripe netted (‘Crimson Sweet’). It would be useful to study g, m, p, and other genes controlling rind pattern, to determine the interactions and develop inbred lines having interesting patterns for the genestock collection.

Resistance genes

Resistance to race 1 and 3 of anthracnose (Colletotrichum lagenarium, formerly Glomerella cingulata var. orbiculare) is controlled by a single dominant gene Ar-1 (Layton, 1937). Resistance to race 2 of anthracnose is also controlled by a single dominant gene Ar-2-1(Winstead et al., 1959). The resistant allele Ar-2-1 is from W695 citron as well as PI 189225, PI 271775, PI 271779, and PI 299379; the susceptible allele ar-2-1 is from ‘Allsweet’, ‘Charleston Gray’, and ‘Florida Giant’; resistance in Citrullus colocynthis is due to other dominant factors, with resistance from R309 and susceptibility from ‘New Hampshire Midget’ (Love and Rhodes, 1988, 1991; Sowell et al., 1980; Suvanprakorn and Norton, 1980; Winstead et al., 1959).

Resistance to race 1 of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. niveum is controlled by a single dominant gene Fo-1 (Henderson et al., 1970; Netzer and Weintall, 1980). Gummy stem blight, caused by Didymella bryoniae (Auersw.) Rehm is inherited by a recessive gene db (Norton, 1979). Watermelons were resistant to older races of Sphaerotheca fuliginea present in the U.S. in the 1970s, but a single recessive gene pm (Robinson et al., 1975) for high susceptibility to powdery mildew was found in the plant introduction, PI 269677. Races 1W and 2W of powdery mildew are now present in the U.S., and induce a susceptible reaction in most cultivars. PI 269677 is highly susceptible to the new races.

Resistance to Papaya ringspot virus-watermelon strain was reported in accessions PI 244017, PI 244019 and PI 485583. It was controlled by a single recessive gene, prv (Guner et al., 2008). A moderate level of resistance to Zucchini yellow mosaic virus was found in four landraces of Citrullus lanatus, but was specific to the Florida strain of the virus. Resistance was conferred by a single recessive gene zym-FL (Provvidenti 1991). A high level of resistance to Zucchini yellow mosaic virus-Florida strain was found in PI 595203 that was controlled by a single recessive gene, zym-FL-2 by (Guner and Wehner 2008). It was not the same as zym-FL because the virus caused a different reaction on PI 482322, PI 482299, PI 482261, and PI 482308. The four accessions were resistant in the study by Provvidenti, but susceptible in the study by Guner and Wehner. Resistance to the China strain of Zucchini yellow mosaic virus was reported in PI 595203, controlled by a single recessive gene zym-CH (Xu et al. 2004). The gene may be allelic to zym-FL-2, but it is difficult to test a segregating F2 progeny for resistance to two different viruses found in different parts of the world.

Xu et al. (2004) reported that PI 595203, which is resistant to ZYMV, was moderately resistant to Watermelon mosaic virus (WMV, formerly Watermelon mosaic virus 2). Strange et al. (2002) reported that PI 595203 also was resistant to Papaya ringspot virus-watermelon strain. The high tolerance to WMV was controlled by at least three recessive genes. Broad-sense heritability was high (0.84 to 0.85, depending on the cross), and narrow-sense heritability was low to high (0.14 to 0.58, depending on the cross).

Genes for insect resistance have been reported in watermelon. Fruit fly (Dacus cucurbitae) resistance was controlled by a single dominant gene Fwr (Khandelwal and Nath, 1978), and red pumpkin beetle (Aulacophora faveicollis) resistance was controlled by a single dominant gene Af (Vashishta and Choudhury, 1972). Stress resistance has been found in watermelon. Seedlings grown at temperatures below 20°C often develop a foliar mottle and stunting. A persistent low temperature is conducive to more prominent foliar symptoms, malformation, and growth retardation. The single dominant gene Ctr was provided cool temperature resistance (Provvidenti, 1992, 2003).

The morphological and resistance genes of watermelon, including gene symbol, synonym, description, references, availability y, and photograph z .

zAsterisks on cultigens and associated references indicate the source of information for each.

yC = Mutant available from Cucurbit Genetics Cooperative watermelon gene curator; M = molecular marker or isozyme; P = mutants are available as standard cultivars or accessions from the plant introduction collection; ? = availability not known; L = mutant has been lost.

The isozymes and molecular markers for watermelon, including gene symbol, synonym, description, references and availability y

Symbol |

Synonym |

Gene description and type lines |

References |

Supplemental references |

Availability |

| Aco-1 | – | Aconitase-1. | Navot et al., 1990 | – | M |

| Aco-2 | – | Aconitase-2. | Navot et al., 1990 | – | M |

| Adh-1 | – | Alcohol dehydrogenase-1; one of five codominant alleles, each regulating one band | Navot and Zamir 1986, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Adh-1-1 | – | Alcohol dehydrogenase-1-1; one of five codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in C; lanatusvar. citroides and C. colocynthis. | Navot and Zamir 1986, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Adh-1-2 | – | Alcohol dehydrogenase-1-2; one of five codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in C. lanatusvar. citroides and C. colocynthis. | Navot and Zamir 1986, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Adh-1-3 | – | Alcohol dehydrogenase-1-3; one of five codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in Praecitrullus fistulosus. | Navot and Zamir 1986, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Adh-1-4 | – | Alcohol dehydrogenase-1-4; one of five codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in Acanthosicyos naudinianus. | Navot and Zamir 1986, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Aps-1 | – | Acid phosphase-1. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir 1986, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Aps-2-1 | – | Acid phosphatase-2-1; one of two codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in C. lanatus and C. colocynthis. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir 1986, 1987 | – | M |

| Aps-2-2 | – | Acid phosphatase-2-2; one of two codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in Acanthosicyos naudinianus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir 1986, 1987 | – | M |

| Dia-1 | – | Diaphorase-1 | Navot et al., 1990 | – | M |

| Est-1 | – | Esterase-1; one of six codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in C. lanatus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987 | – | M |

| Est-1-1 | – | Esterase-1-1; one of six codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in C. lanatus var. citroidesand C. colocynthis. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987 | – | M |

| Est-1-2 | – | Esterase-1-2; one of six codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in C. colocynthis. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987 | – | M |

| Est-1-3 | – | Esterase-1-3; one of six codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in Praecitrullus fistulosus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987 | – | M |

| Est-1-4 | – | Esterase-1-4; one of six codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in C. ecirrhosus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987 | – | M |

| Est-1-5 | – | Esterase-1-5; one of six codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in Acanthosicyos naudinianus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987 | – | M |

| Est-2 | – | Esterase-2; one of five codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in C. lanatus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987 | – | M |

| Est-2-1 | – | Esterase-2-1; one of five codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in C. colocynthis. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987 | – | M |

| Est-2-2 | – | Esterase-2-2; one of five codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in C. colocynthis. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987 | – | M |

| Est-2-3 | – | Esterase-2-3; one of five codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in Praecitrullus fistulosus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987 | – | M |

| Est-2-4 | – | Esterase-2-4; one of five codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in Acanthosicyos naudinianus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987 | – | M |

| Fdp-1 | – | Fructose 1,6 diphosphatase-1. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986 | – | M |

| For-1 | – | Fructose 1,6 diphosphatase-1. | Navot et al., 1990 | – | M |

| Gdh-1 | – | Glutamate dehydrogenase-1; isozyme located in cytosol. | Navot and Zamir, 1986 | – | M |

| Gdh-2 | – | Glutamate dehydrogenase-2; isozyme located in plastids. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986 | – | M |

| Got-1 | – | Glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase-1; one of four codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in C. lanatus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Got-1-1 | – | Glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase-1; one of four codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in C. colocynthis and Praecitrullus fistulosus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Got-1-2 | – | Glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase-1-2; one of four codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in C. lanatus var. citroides. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Got 1-3 | – | Glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase-13; one of four codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in Acanthosicyos naudinianus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Got-2 | – | Glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase-2; one of five codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in C. lanatus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Got-2-1 | – | Glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase-21; one of five codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in C. colocynthis. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Got-2-2 | – | Glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase-22; one of five codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in C. ecirrhosus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Got-2-3 | – | Glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase-2-3; one of five codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in Praecitrullus fistulosus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Got-2-4 | – | Glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase-24; One of five codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in Acanthosicyos naudinianus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Got-3 | – | Glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase-3. | Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Got-4 | – | Glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase-4. | Navot et al., 1990; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| hsp-70 | – | heat shock protein 70; one gene presequence 72-kDa hsp70 is modulated differently in glyoxomes and plastids. | Wimmer et al., 1997 | – | M |

| Idh-1 | – | Isocitrate dehydrogenase-1 | Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Lap-1 | – | Leucine aminopeptidase-1. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986 | – | M |

| Mdh-1 | – | Malic dehydrogenase-1; one of two codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in C. lanatus. | Navot and Zamir, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Mdh-1-1 | – | Malic dehydrogenase-1-1; one of two codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in Praecitrullus fistulosus. | Navot and Zamir, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Mdh-2 | – | Malic dehydrogenase-2; one of three codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in C. lanatus. | Navot and Zamir, 1987 | – | M |

| Mdh-2-1 | – | Malic dehydrogenase-2-1; one of three codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in C. colocynthis. | Navot and Zamir, 1987 | – | M |

| Mdh-2-2 | – | Malic dehydrogenase-2-2; one of three codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in Praecitrullus fistulosus. | Navot and Zamir, 1987 | – | M |

| Me-1 | – | Malic enzyme-1; one of three codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in C. lanatus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Me-1-1 | – | Malic enzyme-1-1; one of three codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in Praecitrullus fistulosus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Me-12 | – | Malic enzyme-12; one of three codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in C. colocynthis. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Me-2 | – | Malic enzyme-2. | Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Pgd-1 | 6 Pgdh-1 | 6-Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase-1; one of three codominant alleles, each regulating one plastid band; found in C. lanatus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Pgd-1-1 | 6 Pgdh-1-1 | 6-Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase-1-1; one of three codominant alleles, each regulating one plastid band; found in Praecitrullus fistulosus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Pgd-1-2 | 6 Pgdh-1-2 | 6-Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase-1-2; one of three codominant alleles, each regulating one plastid band; found in Acanthosicyos naudinianus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Pgd-2 | 6 Pgdh-2 | 6-Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase-2; one of five codominant alleles, each regulating one cytosolic band; found in C. lanatus. | Navot and Zamir, 1986; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Pgd-2-1 | 6 Pgdh-2-1 | 6-Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase-21; one of five codominant alleles, each regulating one cytosolic band; found in C. ecirrhosus. | Navot and Zamir, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Pgd-2-2 | 6 Pgdh-2-2 | 6-Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase-2-2; one of five codominant alleles, each regulating one cytosolic band; found in Praecitrullus fistulosus. | Navot and Zamir, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Pgd-2-3 | 6 Pgdh-2-3 | 6-Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase-2-3; one of five codominant alleles, each regulating one cytosolic band; found in C. colocynthis. | Navot and Zamir, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Pgd-2-4 | 6 Pgdh-2-4 | 6-Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase-2-4; one of five codominant alleles, each regulating one cytosolic band; found in Acanthosicyos naudinianus. | Navot and Zamir, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Pgi-1 | – | Phosphoglucoisomerase-1; one of three codominant alleles, each regulating one plastid band; found in C. lanatus | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987 | – | M |

| Pgi-1-1 | – | Phosphoglucoisomerase-11; one of three codominant alleles, each regulating one plastid band; found in C. colocynthis. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987 | – | M |

| Pgi-1-2 | – | Phosphoglucoisomerase-1-2; one of three codominant alleles, each regulating one plastid band; found in Acanthosicyos naudinianus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987 | – | M |

| Pgi-2 | – | Phosphoglucoisomerase-2; one of six codominant alleles, each regulating one cytosolic band; found in C. lanatus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Pgi-2-1 | – | Phosphoglucoisomerase-2-1; one of six codominant alleles, each regulating one cytosolic band; found in C. lanatus and C. colocynthis. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Pgi-2-2 | – | Phosphoglucoisomerase-2-2; one of six codominant alleles, each regulating one cytosolic band; found in C. ecirrhosus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Pgi-2-3 | – | Phosphoglucoisomerase-2-3; one of six codominant alleles, each regulating one cytosolic band; found inPraecitrullus fistulosus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Pgi-2-4 | – | Phosphoglucoisomerase-2-4; one of six codominant alleles, each regulating one cytosolic band; found in C. lanatus var. citroides. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Pgi-2-5 | – | Phosphoglucoisomerase-2-5; one of six codominant alleles, each regulating one cytosolic band; found in Acanthosicyos naudinianus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Pgm-1 | – | Phosphoglucomutase-1; one of four codominant alleles, each regulating one plastid band; found in C. lanatus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Pgm-1-1 | – | Phosphoglucomutase-1-1; one of four codominant alleles, each regulating one plastid band; found in C. colocynthis. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Pgm-1-2 | – | Phosphoglucomutase-1-2; one of four codominant alleles, each regulating one plastid band; found in Acanthosicyos naudinianus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Pgm-1-3 | – | Phosphoglucomutase-1-3; one of four codominant alleles, each regulating one plastid band; found in Praecitrullus fistulosus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Pgm-2 | – | Phosphoglucomutase-2; one of four codominant alleles, each regulating one cytosolic band; found in C. lanatus. | Navot and Zamir, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Pgm-2-1 | – | Phosphoglucomutase-2-1; one of four codominant alleles, each regulating one cytosolic band; found in Acanthosicyos naudinianus. | Navot and Zamir, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Pgm-2-2 | – | Phosphoglucomutase-2-2; one of four codominant alleles, each regulating one cytosolic band; found in C. lanatus. | Navot and Zamir, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Pgm-2-3 | M | Phosphoglucomutase-2-3; one of four codominant alleles, each regulating one cytosolic band; found in Praecitrullus fistulosus. | Navot and Zamir, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Prx-1 | – | Peroxidase-1; one of seven codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in C. lanatus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987 | – | M |

| Prx-11 | – | Peroxidase-11; one of seven codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in C. colocynthis. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987 | – | M |

| Prx-12 | – | Peroxidase-12; one of seven codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in Praecitrullus fistulosus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987 | – | M |

| Prx-13 | – | Peroxidase-13; one of seven codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in C. lanatus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987 | – | M |

| Prx-14 | – | Peroxidase-14; one of seven codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in C. ecirrhosus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987 | – | M |

| Prx-15 | – | Peroxidase-15; one of seven codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in C. lanatus and C. colocynthis. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987 | – | M |

| Prx-16 | – | Peroxidase-16; one of seven codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in Acanthosicyos naudinianus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987 | – | M |

| Prx-2 | – | Peroxidase-2. | Navot and Zamir, 1987 | – | M |

| Prx-3 | – | Peroxidase-3. | Navot and Zamir, 1987 | – | M |

| Sat | – | Serine acetyltransferase; catalyzes the formation of O-acetylserine from serine and acetyl-CoA. | Saito et al., 1997 | – | M |

| Skdh-1 | – | Shikimic acid dehydrogenase-1. | Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Skdh-2 | – | Shikimic acid dehydrogenase-2; one of six codominant alleles, each regulating one band. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987 | – | M |

| Skdh-21 | – | Shikimic acid dehydrogenase-21; one of six codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in C. colocynthis. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987 | – | M |

| Skdh-22 | – | Shikimic acid dehydrogenase-22; one of six codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in C. colocynthis. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987 | – | M |

| Skdh-23 | – | Shikimic acid dehydrogenase-23; one of six codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in Acanthosicyos naudinianus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987 | – | M |

| Skdh-24 | – | Shikimic acid dehydrogenase-24; one of six codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in C. ecirrhosus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987 | – | M |

| Skdh-25 | – | Shikimic acid dehydrogenase-25; one of six codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in Praecitrullus fistulosus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987 | – | M |

| Sod-1 | – | Superoxide dismutase-1; one of three codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in C. lanatus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Sod-11 | – | Superoxide dismutase-11; one of three codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in C. colocynthis. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Sod-12 | – | Superoxide dismutase-12; one of three codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in Acanthosicyos naudinianus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987; Zamir et al., 1984 | – | M |

| Sod-2 | – | Superoxide dismutase-2; one of two codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in C. lanatus. | Navot and Zamir, 1987 | – | M |

| Sod-21 | – | Superoxide dismutase-21; one of two codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found inAcanthosicyos naudinianus. | Navot and Zamir, 1987 | – | M |

| Sod-3 | – | Superoxide dismutase-3; one of two codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in C. lanatus. | Navot and Zamir, 1987 | – | M |

| Sod-31 | – | Superoxide dismutase-31; one of two codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in Praecitrullus fistulosus. | Navot and Zamir, 1987 | – | M |

| Spr-1 | – | Seed protein-1. | Navot and Zamir, 1986 | – | M |

| Spr-2 | – | Seed protein-2. | Navot and Zamir, 1986 | – | M |

| Spr-3 | – | Seed protein-3. | Navot and Zamir, 1986 | – | M |

| Spr-4 | Spr-4 | Seed protein-4. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986 | – | M |

| Spr-5 | Spr-5 | Seed protein-5. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986 | – | M |

| Tpi-1 | – | Triosephosphatase isomerase-1. one of four codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in C. lanatus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987 | – | M |

| Tpi-11 | – | Triosephosphatase isomerase-11; one of four codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in C. colocynthis. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987 | – | M |

| Tpi-12 | – | Triosephosphatase isomerase-12; one of four codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in Praecitrullus fistulosus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987 | – | M |

| Tpi-13 | – | Triosephosphatase isomerase-13; one of four codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in Acanthosicyos naudinianus. | Navot et al., 1990; Navot and Zamir, 1986, 1987 | – | M |

| Tpi-2 | – | Triosephosphatase isomerase-2; one of three codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in C. lanatus. | Navot and Zamir, 1987 | – | M |

| Tpi-21 | – | Triosephosphatase isomerase-21; one of three codominant alleles, each regulating one band; found in Acanthosicyos naudinianus. | Navot and Zamir, 1987 | – | M |

| Ure-1 | – | Ureaase-1. | Navot and Zamir, 1987 | – | M |

y C = Mutant available from Cucurbit Genetics Cooperative watermelon gene curator; M = molecular marker or isozyme; P = mutants are available as standard cultivars or accessions from the plant introduction collection; ? = availability not known; L = mutant has been lost.

Literature Cited

- Bang, H., S.R. King and W. Liu. 2006. A new male sterile mutant identified in watermelon with multiple unique morphological features. Cucurbit Genet. Coop. Rpt. 28-29: 47-48.

- Barham, W.S. 1956. A study of the Royal Golden watermelon with emphasis on the inheritance of the chlorotic condition characteristic of this variety. Proc. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 67: 487-489.

- Boyhan, G., J.D. Norton, B.J. Jacobsen, and B.R. Abrahams. 1992. Evaluation of watermelon and related germ plasm for resistance to zucchini yellow mosaic virus. Plant Dis. 76: 251-252.

- Chambliss, O.L., H.T. Erickson and C.M. Jones. 1968. Genetic control of bitterness in watermelon fruits. Proc. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 93: 539-546.

- Cucurbit Gene List Committee. 1979. New genes for the Cucurbitaceae. Cucurbit Genet. Coop. Rpt. 2: 49-53.

- Cucurbit Gene List Committee. 1982. Update of cucurbit gene list and nomenclature rules. Cucurbit Genet. Coop. Rpt. 5: 62-66.

- Cucurbit Gene List Committee. 1987. Gene list for watermelon. Cucurbit Genet. Coop. Rpt. 10: 106-110.

- Desbiez, C. and H. Lecoq. 1997. Zucchini yellow mosaic virus. Plant Path. 46: 809-829.

- Dyutin, K.E. and E.A. Afanas’eva. 1987. Inheritance of the short vine trait in watermelon. Cytology Genetics (Tsitologiya i Genetika) 21: 71-73.

- Dyutin, K.E. and S.D. Sokolov. 1990. Spontaneous mutant of watermelon with male sterility. Cytology Genetics (Tsitologiya i Genetika) 24: 56-57.

- El-Hafez, A.A.A., A.K. Gaafer, and A.M.M. Allam. 1981. Inheritance of flesh color, seed coat cracks and total soluble solids in watermelon and their genetic relations. Acta Agron. Acad. Hungaricae 30: 82-86.

- Guner, N., Z. PesicVan-Esbroeck, and T.C. Wehner. 2008a. Inheritance of resistance to Papaya ringspot virus-watermelon strain in watermelon. J. Hered. (in review).

- Guner, N., Z. PesicVan-Esbroeck, and T.C. Wehner. 2008b. Screening for resistance to Zucchini yellow mosaic virus in 1654 watermelon cultivars and plant introduction accessions. Crop Sci. (in review).

- Gusmini, G., T.C. Wehner, and R.L. Jarret. 2004. Inheritance of egusi seed type in watermelon. J. Hered. 95: 268-270.

- Gusmini, G. and T.C. Wehner. 2006. Qualitative inheritance of rind pattern and flesh color in watermelon. J. Hered. 97: 177-185.

- Hall, C.V., S.K. Dutta, H.R. Kalia and C.T. Rogerson. 1960. Inheritance of resistance to the fungus Colletotrichum lagenarium(Pass.) Ell. and Halst. in watermelons. Proc. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 75: 638-643.

- Henderson, W.R. 1989. Inheritance of orange flesh color in watermelon. Cucurbit Genet. Coop. Rpt. 12: 59-63.

- Henderson, W.R. 1991. Gene List for Watermelon. Cucurbit Genet. Coop. Rpt. 14: 129-138.

- Henderson, W.R. 1992. Corrigenda to the 1991 Watermelon Gene List (CGC 14:129-137). Cucurbit Genet. Coop. Rpt. 15: 110.

- Henderson, W.R., S.F. Jenkins, Jr. and J.O. Rawlings. 1970. The inheritance of Fusarium wilt resistance in watermelon, Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Mansf. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 95: 276-282.

- Henderson, W.R., G.H. Scott and T.C. Wehner. 1998. Interaction of flesh color genes in watermelon. J. Hered. 89: 50-53.

- Huang, H., X. Zhang, Z. Wei, Q. Li, and X. Li. 1998. Inheritance of male-sterility and dwarfism in watermelon [Citrullus lanatus(Thunb.) Matsum. and Nakai]. Scientia Horticulturae 74: 175-181.

- Jiang, X.T. and D.P. Lin. 2007. Discovery of watermelon gynoecious gene, gy. Acta Hort. Sinica 34: 141-142.

- Kanda, T. 1951. The inheritance of seed-coat colouring in the watermelon. Jap. J. Genet. 7: 30-48.

- Khandelwal, R.C. and P. Nath. 1978. Inheritance of resistance to fruit fly in watermelon. Can. J. Genet. Cytol. 20: 31-34.

- Kumar, R. and T. C. Wehner. 2011. Discovery of second gene for solid dark green versus light green rind pattern in watermelon. J. Heredity.

- Kwon, Y.S. and F. Dane. 1999. Inheritance of green flower color (gf) in watermelon (Citrullus lanatus). Cucurbit Genet. Coop. Rpt. 22: 31-33.

- Layton, D.V. 1937. The parasitism of Colletotrichum lagenarium (Pass.) Ells. and Halst. Iowa Agr. Expt. Sta. Ann. Bul. 223.

- Lecoq, H. and D.E. Purcifull. 1992. Biological variability of potyviruses, an example: zucchini yellow mosaic virus. Arch. Virol. Suppl. 5: 229-234.

- Lin, D., T. Wang, Y. Wang, X. Zhang and B.B. Rhodes. 1992. The effect of the branchless gene bl on plant morphology in watermelon. Cucurbit Genet. Coop. Rpt. 15: 74-75.

- Liu, P.B.W. and J.B. Loy. 1972. Inheritance and morphology of two dwarf mutants in watermelon. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 97: 745-748.

- Love, S.L. and B.B. Rhodes. 1988. Single gene control of anthracnose resistance in Citrullus? Cucurbit Genet. Coop. Rpt. 11: 64-67.

- Love, S.L. and B.B. Rhodes. 1991. R309, a selection of Citrullus colocynthis with multigenic resistance to Colletotrichum lagenariumrace 2. Cucurbit Genet. Coop. Rpt. 14: 92-95.

- McKay, J.W. 1936. Factor interaction in Citrullus. J. Hered. 27: 110-112.

- Mohr, H.C. 1953. A mutant leaf form in watermelon. Proc. Assn. Southern Agr. Workers 50: 129-130.

- Mohr, H.C. 1956. Mode of inheritance of the bushy growth characteristics in watermelon. Proc. Assn. Southern Agr. Workers 53: 174.

- Mohr, H.C. and M.S. Sandhu. 1975. Inheritance and morphological traits of a double recessive dwarf in watermelon, Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Mansf. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 100: 135-137.

- Navot, N., M. Sarfatti and D. Zamir. 1990. Linkage relationships of genes affecting bitterness and flesh color in watermelon. J. Hered. 81: 162-165.

- Navot, N. and D. Zamir. 1986. Linkage relationships of 19 protein coding genes in watermelon. Theor. Appl. Genet. 72: 274-278.

- Navot, N. and D. Zamir. 1987. Isozyme and seed protein phylogeny of the genus Citrullus (Cucurbitaceae). Plant Syst. & Evol. 156: 61-67.

- Netzer, D. and C. Weintall. 1980. Inheritance of resistance to race 1 of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. niveum. Plant Dis. 64: 863-854.

- Norton, J.D. 1979. Inheritance of resistance to gummy stem blight in watermelon. HortScience 14: 630-632.

- Poole, C.F. 1944. Genetics of cultivated cucurbits. J. Hered. 35: 122-128.

- Poole, C.F. and P.C. Grimball. 1945. Interaction of sex, shape, and weight genes in watermelon. J. Agr. Res. 71: 533-552.

- Poole, C.F. P.C. Grimball and D.R. Porter. 1941. Inheritance of seed characters in watermelon. J. Agr. Res. 63: 433-456.

- Porter, D.R. 1937. Inheritance of certain fruit and seed characters in watermelons. Hilgardia 10: 489-509.

- Provvidenti, R. 1986. Reactions of PI accessions of Citrullus colocynthis to zucchini yellow mosaic virus and other viruses. Cucurbit Genet. Coop. Rpt. 9: 82-83.

- Provvidenti, R. 1991. Inheritance of resistance to the Florida strain of zucchini yellow mosaic virus in watermelon. HortScience 26(4): 407-408.

- Provvidenti, R. 1992. Cold resistance in accessions of watermelon from Zimbabwe. Cucurbit Genet. Coop. Rpt. 15: 67-68.

- Provvidenti, R. 1994. Inheritance of a partial chlorophyll deficiency in watermelon activated by low temperatures at the seedling stage. HortScience 29(9): 1062-1063.

- Provvidenti, R. 2003. Naming the gene conferring resistance to cool temperatures in watermelon. Cucurbit Genet. Coop. Rpt. 26 (in press).

- Ray, D.T. and J.D. Sherman. 1988. Desynaptic chromosome behavior of the gms mutant in watermelon. J. Hered. 79: 397-399.

- Rhodes, B.B. 1986. Genes affecting foliage color in watermelon. J. Hered. 77: 134-135.

- Rhodes, B. and X. Zhang. 1995. Gene list for watermelon. Cucurbit Genetics Coop. Rpt. 18: 69-84.

- Rhodes, B. and F. Dane. 1999. Gene list for watermelon. Cucurbit Genetics Coop. Rpt. 22: 61-74.

- Rhodes, B.B., X.P. Zhang, V.B. Baird, and H. Knapp. 1999. A tendrilless mutant in watermelon: phenotype and inheritance. Cucurbit Genetics Coop. Rpt. 22: 28-30.

- Robinson, R.W., H.M. Munger, T.W. Whitaker and G.W. Bohn. 1976. Genes of the Cucurbitaceae. HortScience 11: 554-568.

- Robinson, R.W., R. Provvidenti and J.W. Shail. 1975. Inheritance of susceptibility to powdery mildew in the watermelon. J. Hered. 66: 310-311.

- Rosa, J.T. 1928. The inheritance of flower types in Cucumis and Citrullus. Hilgardia 3: 233-250.

- Saito, K., K. Inoue, R. Fukushima, and M. Noji. 1997. Genomic structure and expression analyses of serine acetyltransferase gene in Citrullus vulgaris (watermelon). Gene 189: 57-63.

- Shimotsuma, M. 1963. Cytogenetical studies in the genus Citrullus. VII. Inheritance of several characters in watermelons. Jap. J. Breeding 13: 235-240.

- Sowell, G., Jr., B.B. Rhodes and J.D. Norton. 1980. New sources of resistance to watermelon anthracnose. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 105: 197-199.

- Suvanprakorn, K. and J.D. Norton. 1980. Inheritance of resistance to anthracnose race 2 in watermelon. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 105: 862-865.

- Strange, E.B., N. Guner, Z. Pesic-VanEsbroeck, and T.C. Wehner. 2002. Screening the watermelon germplasm collection for resistance to Papaya ringspot virus type-W. Crop Sci. 42: 1324-1330.

- Tanaka, T., S. Wimol, and T. Mizutani. 1995. Inheritance of fruit shape and seed size of watermelon. J. Japan. Soc. Hort. Sci. 64(3): 543-548.

- Vashishta, R.N. and B. Choudhury. 1972. Inheritance of resistance to red pumpkin beetle in muskmelon, bottle gourd and watermelon. Proc. 3rd Intern. Symposium Sub-Trop. Hort. 1:75-81.

- Warid, A. and A.A. Abd-El-Hafez. 1976. Inheritance of marker genes of leaf color and ovary shape in watermelon, Citrullus vulgarisSchrad. The Libyan J. Sci. 6A: 1-8.

- Watts, V.M. 1962. A marked male-sterile mutant in watermelon. Proc. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 81: 498-505.

- Watts, V.M. 1967. Development of disease resistance and seed production in watermelon stocks carrying the msg gene. Proc. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 91: 579-583.

- Weetman, L.M. 1937. Inheritance and correlation of shape, size, and color in the watermelon, Citrullus vulgaris Schrad. Iowa Agr. Expt. Sta. Res. Bul. 228: 222-256.

- Wimmer, B., F. Lottspeich, I. van der Klei, M. Veenhuis, and C. Gietl. 1997. The glyoxysomal and plastid molecular chaperones (70-kDa heat shock protein) of watermelon cotyledons are encoded by a single gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94: 13624-13629.

- Winstead, N.N., M.J. Goode and W.S. Barham. 1959. Resistance in watermelon to Colletotrichum lagenarium races 1, 2, and 3. Plant Dis. Rptr. 43: 570-577.

- Xu, Y., D. Kang, Z. Shi, H. Shen, and T.C. Wehner. 2004. Inheritance of resistance to zucchini yellow mosaic virus and watermelon mosaic virus in watermelon. J. Hered. 96: 498-502.

- Yang, D.H. 2006. Spontaneous mutant showing pale seedling character in watermelon (Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Matsum. and Nakai). Cucurbit Genet. Coop. Rpt. 28-29: 49-51.

- Zamir, D., N. Navot and J. Rudich. 1984. Enzyme polymorphism in Citrullus lanatus and C. colocynthis in Israel and Sinai. Plant Syst. & Evol. 146: 163-170.

- Zhang, J. 1996. Inheritance of seed size from diverse crosses in watermelon. Cucurbit Genetics Coop. Rpt. 19: 67-69.

- Zhang, X.P. and M. Wang. 1990. A genetic male-sterile (ms) watermelon from China. Cucurbit Genetics Coop. Rpt. 13: 45.

- Zhang, X.P. Rhodes, B.B and M. Wang. 1994a. Genes controlling watermelon seed size. Cucurbitaceae ’94: Evaluation and Enhancement of Cucurbit Germplasm, p. 144-147 (eds. G. Lester and J. Dunlap). ASHS Press, Alexandria, Virginia.

- Zhang, X.P., H.T. Skorupska and B.B. Rhodes. 1994b. Cytological expression in the male sterile ms mutant in watermelon. J. Heredity 85:279-285.

- Zhang, X.P., B. B. Rhodes, V. Baird and H. Skorupska. 1996a. A tendrilless mutant in watermelon: phenotype and development. HortScience 31(4): 602 (abstract).

- Zhang, X.P., B.B. Rhodes and W.C. Bridges. 1996b. Phenotype, inheritance and regulation of expression of a new virescent mutant in watermelon: juvenile albino. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 121(4): 609-615.