Cucurbit Genetics Cooperative Report 23:126-127 (article43) 2000

Herwig Teppner

Institute of Botany, Karl-Franzens-University, Hoilteigasse 6, A-8010, Graz, Austria; [email protected]

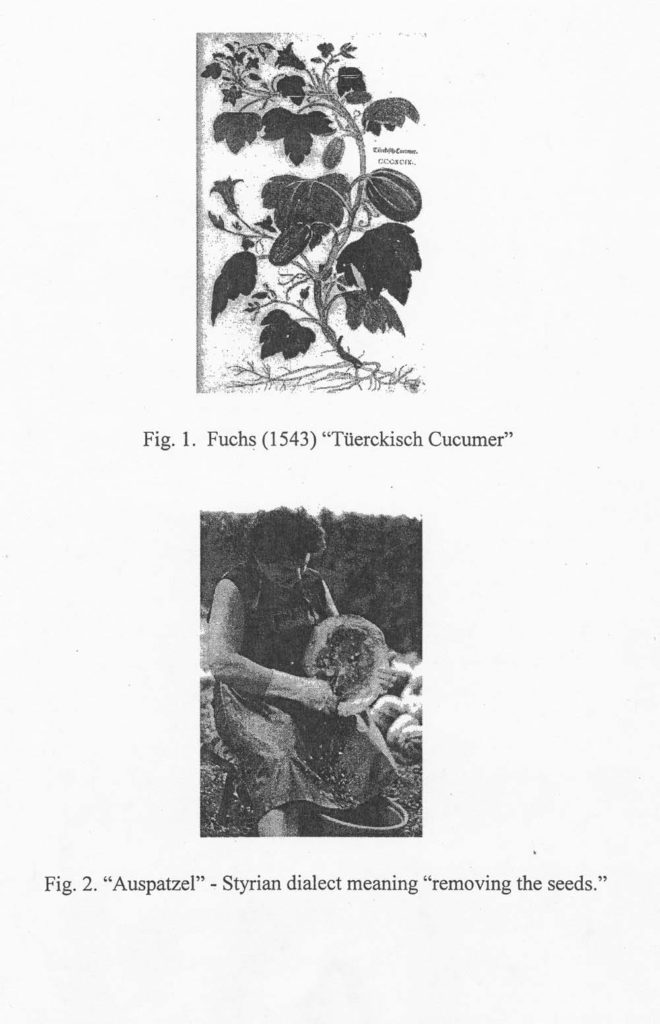

From the herbals of the 16th century it can be shown, that horticultural groups of Cucurbita pepo L. subsp. pepo (pumpkin, vegetable marrow) and of C. pepo L. subsp. ovifera (L.) Decker (scallop, acron, ornamental gourds) were already present at this time in europe, to allow rapid evolution of new cultivars (Fig. 1). Because of the scarcity of vegetable oils and fats in parts of Central Europe during these ages, the appearance of a pumpkin with its large, oil-rich seeds, was a welcome relief. So after this discovery of the New World, pumpkin spread quickly over the Old World as a vegetable and in some regions also as an oil plant. The first step in traditional processing of pumpkin seeds for oil production in Styria (Austria, Central europe) was peeling the seeds from the thick seed coat. The first reliable record for such peeled seeds dates back from the year 1735 (5).

The appearance of the thin coated mutant simplified the processing greatly (Fig. 2). The exact time of appearance is not known. In the penible report of the agricultural situation in Styria of Hlubek 1860 (3) only the peeling of seeds but no thin coated seeds, which can be processed without peeling, are mentioned. Even in the famous agricultural flora of Alefeld 1866 (1) from the 66 cultivars of C. pepo no thin coated type is mentioned. On the other hand, the search of the pumpkin breeders Tschermak-Seysenegg and Buchinger in the 30’s and 40’s lead them to the opinion that it was present at ca. 1880. thus we can estimate, that the Vinous Styrian Oil Pumpkin (C. pepo L. subsp. pepo var. styriaca Greb.) segregated between c. 1870 and 1880 in the region of Styria from the normal field pumpkin of that time (8, 2, 6, 7).

The most important characteristic of var. styriaca is the lack of any lignification in the seed coat, whereas in the normal thick coated C. pepo the four outer ones of the five seed coat layers are strongly lignified. In the modern literature the prevailing opinion is that, that only one gene (N/n) is responsible for this character, see e.g. the gene list of Hutton & al. (4). Under this circumstance it would be difficult to understand, why such a mutation occurred only once. The discovery of a mutant with a so-called semi-thin seed coat and the segregation in a thin x semi-thin cross lead the author to estimate that at least six genes much be responsible for the seed coat characteristics. In this case, an allele combination which gives rise to the very special thin seed coat phenotype of var. styriaca must be very understandable.

This paper is published in full length, with 46 figures and c. 100 references in Phyton (Horn, Austria) 40(1) (2000).

Literature Cited

- Alefeld, F. 1866. Landwirthschaftliche Flora oder die nutzbaren kultivirten Garten- und Feldgewachse Mitteleuropa’s. Berlin.

- Buchinger, A. 1944. Kurbiszuchtung. Zuchter. 16 (4-6): 75-85.

- Hlubek, F.X. 1860. ein treues Bild des Herzogthumes Steiermark Graz.

- Hutton, M.G. and Robinson, R.W. 1992. Gene List for cucurbita spp. Cucurbit Genetics Coop. Rpt. 15:102-109.

- Kundegraber,M. 1988. Die volkstumliche Ernahrung im Lichte der Untertaneninventare. Am Beispiel der Herrschaft Stainz. Z. Histor. Verein. Steierm. 79:187-193.

- Teppner, H. 1982. Der Steirische Olkurbis und cinge fruhe Quellen uber Kurbisanbau. In: Teppner, H. (ed.) Die Koralpe. Beitrage zur Botanik, Geologie, Klimatologie und Volkskunde. Graz. 57-63.

- Teppner, H. 1999. Noitzen zur Geschichte des Kurbisses. Obst, Wein, Garten (Graz). 68(10):36.

- Tschermak-Seysenegg, E. 1934. Der Kurbis mit schalenlosen Samen, eine beachtenswerte Oelfrucht. Wiener Landwirtschaftl. Zeitung. 1934 (7): 41-42, (8): 48-49.